When will we know if lifting lockdowns is “working,” and what would prompt us to fall back into additional lockdowns?

In the countries and U.S. states that implemented well crafted “reopening” plans, the scientific and medical criteria that convinced their governments it was safe to lift lockdowns to allow their people to go back to work are the same that should be monitored on an ongoing basis to prevent any relapse.

What are these criteria? Let’s review the ones that are most commonly being used in European countries and many U.S. states to start lifting lockdowns and reopening their economies:

- In terms of public health data, government officials track the new daily Covid-19 cases, and whether they keep declining over a two weeks period: This is one of the most basic indicators used to end lockdowns, to confirm that the Covid-19 infections “curve” has “flattened.”

- The number of new daily Coronavirus cases should also be significantly below its peak, by at least 50%, and not increase week by week above a pre-set level.

- Another fundamental set of criteria relate to hospital and healthcare capacity, since fear of overwhelming hospitals and care providers was the determining factor for governments to issue stay-at-home orders. In that category one can find the percentage of hospital and ICU beds being used relative to capacity; the percentage of patients coming to hospitals for tests actually admitted to the ER; and of course, availability of PPE equipment for all medical staff.

- Widespread testing for Coronavirus should also be facilitated and tracked by governments. But when do we know we are testing enough? When a small percentage of the tests come back positive for Covid-19: In countries like Australia; New Zealand; South Korea; Austria; the Czech Republic; Denmark; Germany; Finland; and Norway that have implemented successful testing program, this percentage is in the 3%-6% range. In the U.S. it is still at 20% in most states, far too high. To bring our population testing levels to those of the countries mentioned above, we need to start testing—soon—two to three million people every day.

- But the indicator that tells us most directly whether we are safe out of lockdown, or conversely at risk to fall back into it, is the rate of Covid-19 reinfection, often called R0: As long as this R0 rate of new infections per infected person remains below 1.0, we are safe. Last week, after Germany started implementing its gradual go back to work plan, the country’s R0 increased after a few days—an alarm bell taken very seriously by the local government and health authorities, until the ratio fell back again.

Where is this all working? Examples of success include Australia and New Zealand, where new cases of Coronavirus have essentially fallen to zero—virus eradicated locally. South Korea and its early widespread testing is also a Covid-19 success story, as are Hong Kong and Taiwan. In Europe, early lockdowns and rigorous testing have allowed Austria; the Czech Republic; Denmark; Germany; Finland; and Norway to return to work—albeit gradually. In the U.S., large states like Florida, Texas and Georgia are ending their lockdowns without meeting the above defined criteria, e.g. Coronavirus cases are still increasing in Texas. On the other hand, California, Oregon and Washington State are planning to end their lockdowns gradually within 2-4 weeks, while adhering to most of the above criteria.

Lifting lockdowns following scientific and health criteria is critical to avoid a “W” type of Covid-19 infection curve, with a second wave occurring this fall, with lots of new fatalities. This is what happened during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, when the second wave of infections actually led to many more deaths than during the first wave.

Should the number of Coronavirus start spiking again, exponentially; deaths due to the virus increase substantially; local hospitals starting to run out of ICU beds, with their medical staff overburdened; testing still indicating a high percentage of those tested carrying the virus; and an R0 going back above 1.0, it would be clear to local governments and health officials that additional lockdowns would have to be ordered, a bad situation. Local economies could be badly hurt as a result, with consumer confidence evaporating.

An example of a real-life test of the use of quantitative criteria to decide re-entering lockdown can be found in the Thuringia region (“Lander”) in central Germany. According to the German weekly magazine Der Spiegel and the Robert Koch public health institute, the Greiz commune in Thuringia is the only commune in Germany where the agreed-upon weekly limit of 50 new Covid-19 infections per 100,000 habitants has been exceeded. The commune leaders are talking to the Lander authorities to decide whether this surge in new virus infections, attributable to a senior living institution, should lead to an application of what Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel calls “the emergency brake,” leading the commune to fall back into lockdown.

To avoid this risk of a deadly “second wave,” return to work should be gradual, with protective equipment (masks, etc.) available to the whole population, not just essential workers. The first industries to be reopened should be the ones where social distancing guidelines are easiest to achieve: Construction and infrastructure work are excellent examples of this. Hospitals should be allowed to perform elective procedures to attend patients—and shore-up their much-challenged finances. Child care, kindergartens and primary schools should also be open so that parents can go to work without having to worry about young children home alone. Many small retail outlets could open too, with a very limited number of customers allowed inside (one to two per thousand sq. ft.), and with lots of curb-side merchandise pick-up. Bars, restaurants, barber shops, hairdressers and body salons are examples of businesses that should be open later, and with realistic social distancing measures well defined in advance—exactly the contrary of what happened in Georgia, where those were the first to open (with very few customers).

To keep the lifting of lockdowns safe over the period of time (one year? two years?) needed for Covid-19 vaccines to be developped, new business models and operating processes will have to be engineered: Just like most restaurants will likely have to operate with fewer tables to allow social distancing, many units of manufacturing production will have to adapt to create safe conditions for their workers. For example, the U.S. CDC has written extensive guidelines to allow Coronavirus challenged meat-packing plants to operate safely, including employee screening; workplace cleaning; frequent hand washing; and re-designed floor spaces and processes to allow workers to be safely distant from one another, including a slower speed of the assembly lines. When worker health safety has proven to be an issue, these CDC guidelines should become mandatory, not “voluntary” for the businesses and companies concerned. Otherwise the very employees needed to reopen the economy will become new victims of the virus and potential casualties, leading to the opposite economic outcome that ending lockdowns intended in the first place.

The criteria, health indicators and population statistics that tell us the lifting of lockdowns is “working” in a safe manner for all are well defined. We need to monitor them on an ongoing basis and follow a new set of processes at work that will keep people safe and prevent us from falling back into additional lockdowns. It can certainly be achieved, but requires discipline, both at the decision-makers’ level and within our population.

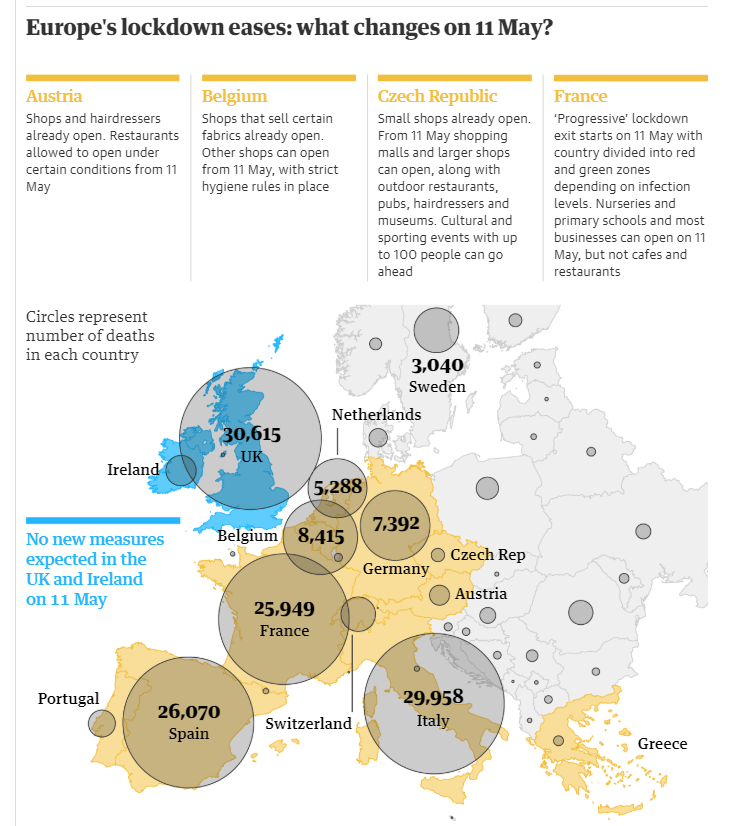

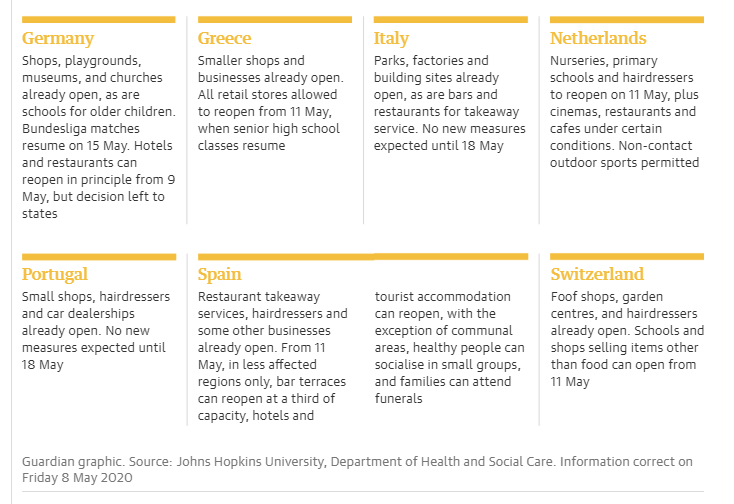

Note: Below is an excellent synopsis of lockdown eases—many starting on May 11—throughout Europe, from The Guardian.

Tags: Australia, Austria, California, Coronavirus, Covid-19, Denmark, economy, Finland, Georgia, Germany, healthcare, Lockdown, New Zealand, Norway, Pandemic, Public health, South Korea, Texas, U.S. States, US political trends, Washington State