A primer on Dodd-Frank, through a simple Q&A

- Why was Dodd Frank passed?

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was passed by Congress, and signed by president Obama on July 21st, 2010, to stabilize our banking and financial system, and prevent a repeat of the disastrous 2008 financial crisis, which led to the “Great Recession.”

The act’s many provisions were spelled out over 2,300 pages or so, and were to be implemented over a period of several years. The act also established a number of new government agencies tasked with oversight of the various components of the act. The Financial Stability Oversight Council and Orderly Liquidation Authority monitors the financial stability of the largest U.S. financial institutions, like banking giants JP Morgan or Wells Fargo, which are deemed “too big to fail.” The Council has the authority (not used yet) to break-up banks that are so large as to pose a systemic risk to our financial system if they become dangerously unstable. The Council can also force these “too big to fail” banks to increase their reserve requirements, something it has done in a few occasions already. Increasing reserve requirements means banks must hold a higher percentage of their assets in cash, which decreases the amounts they can hold in marketable securities, and their market-making power. In the potential case of break-up, restructuring or liquidation, the Orderly Liquidation Fund would provide money to assist with the dismantling of the affected financial companies, to prevent taxpayer dollars to be used to prop up such entities.

Another key component of Dodd-Frank was the Volcker rule, named after former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker. This federal regulation prohibited banks from conducting certain investment activities within their own accounts, and limited their ownership of and relationships with private equity and hedge funds. The Volcker rule thus curtailed a financial institution’s ability to engage in speculative trading strategies with retail clients’ government insured deposits. The idea was to eliminate conflicts of interest by not allowing banks to engage in vast amounts of proprietary trading, i.e. for their own account, unless they used their own equity, or had enough “skin in the game.” No less than five federal agencies (The Federal Reserve System; the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, or FDIC; the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency; the Commodity Futures Trading Commission; and the Security and Exchange Commission, or SEC) approved the final version of the Volcker rule in 2014. Some original provisions of the rule were somewhat diluted, allowing banks more leeway in their investment and trading activities. But clearly the Volcker rule was an attempt within Dodd-Frank to emulate the Great Depression Glass-Steagall Act, a very simple, short (37 pages) and precise piece of legislation recognizing the financial risks of financial institutions engaging in commercial and investment banking at the same time.

During his successful 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump campaigned on the need to curtail financial speculation of Wall Street, and advocated a return to Glass-Steagall, which clearly separated retail, or “main street” banking activities, from investment banking and more speculative financial activities. However, the Trump administration did not follow-up on this campaign promise, opposed by most financial institutions in the US.

Dodd-Frank regulated the financial institutions’ use of derivatives as well, such as the credit default swaps that contributed so much to the 2008 financial crisis. It did so through the set up of centralized exchanges for swaps trading. This reduced the possibility of counterparty default, and provided greater disclosure of swaps trading information to increase transparency in those markets. This aspect of the act led to much recrimination from financial institutions and their lobbyists. An additional feature of Dodd-Frank was the creation of the SEC Office of Credit Ratings, which was tasked with ensuring that agencies improved their accuracy in rating financial instruments, businesses, municipalities, and other entities evaluated by them. The reliability of this rating activity had been much criticized after 2008, credit rating agencies being accused of giving far too many misleading favorable investment ratings. Dodd-Frank also strengthened the “whistleblower” program, and executive pay claw back provisions enacted by the earlier Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

As legislation, Dodd Frank was like the celebrated Sagrada Familia basilica by Gaudi in Barcelona, Spain: ambitious, striking, but far from a completed work.

In addition, the Trump administration and the Republican led Congress have taken a number of steps to weaken Dodd-Frank, “to improve liquidity and credit in our financial system.” In the spring of 2018, the U.S. Senate approved a bill, by a rare bi-partisan majority of 67 votes against 32, which exempts a large number of “medium-sized” financial companies, with assets between $50 billion and $250 billion, from the toughest banking regulations under Dodd Frank. These banks are no longer labeled “too big to fail” and no longer need to undergo a yearly stress test to prove they could overcome successfully another financial crisis like the one in 2008. So only the very largest US banks, such as JP Morgan, Bank of America, Citicorp and Wells Fargo, are now subject to the most stringent features of Dodd Frank. Proponents of this “watering down” of Dodd Frank say that the new legislation brings “relief” from regulations to regional banks that are relatively small in size compared to huge institutions like JP Morgan. Opponents say that this bill increases the risk of another financial crisis, by letting risky lending and investing go unregulated at a time when financial assets are being bid-up, like happened before 2008.

- Why is Dodd Frank important for customers?

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was established as part of Dodd-Frank to protect consumers, principally in the area of “predatory” mortgage lending.

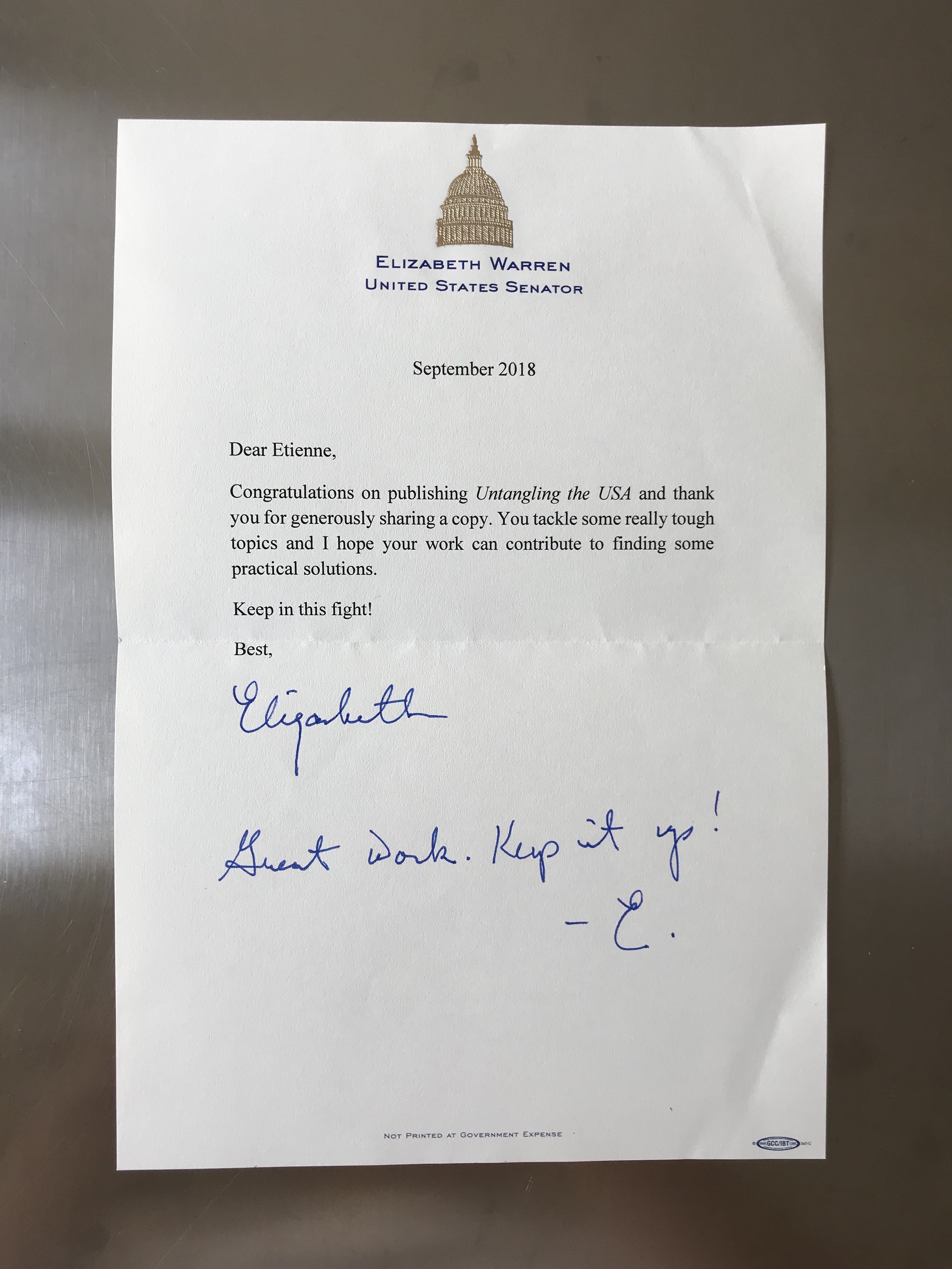

As such, it reflected the widespread sentiment that the subprime market and its reliance on shaky mortgages was the main cause of the 2008 disaster. Among other things, the CFPB prevented mortgage originators from steering potential borrowers to the loan that will result in the highest payment for the originator. The CFPB also set new rules in consumer lending, credit and debit cards, as well as for financial brokers. It required lenders to disclose information in a form that was easy for all consumers to understand, even for auto loans. Credit card applications were made simpler as a result. Setting up the CFPB met with fierce financial industry and political opposition. One result of this opposition was that the Obama administration was unable to name as head of the CFPB its most enthusiastic proponent and early architect, Massachusetts’s Senator Elizabeth Warren.

In September of 2016, the CFPB attained national recognition with consumers, in the wake of the Wells Fargo fake banking and credit card account scandal.

Thousands of the bank’s retail banking employees had literally created one and a half million new accounts since 2011, under the much-hailed bank’s strategy of “cross-selling.” This strategy was one of the reasons the Wells stock had gone up faster than its peers during the aftermath of the financial crisis. The problem, as explained by the CFPB in its report, was that most of these new accounts had been created without their owners knowing about it. These phantom accounts allowed thousands of Wells Fargo employees to meet their sales quotas, but led to lots of additional account fees for the bank’s retail customers, who new nothing about this. Wells Fargo, a company employing about 300,000 people, was fined $185 million, a relatively minor sum in today’s banking world.

The bank initially fired 5,300 employees, most of them at the bottom of the totem pole, with no senior executive affected whatsoever, not even the head of the retail banking division Carrie Tolstedt, who had retired in the summer with an eight figure package. However, given that thousands of small retail consumers of the bank were defrauded, the scandal was enormous. Wells lost $18billion in market capitalization in a matter of days. Chairman and CEO John Stumpf was hauled in front of Congress for a bi-partisan grilling, with Senator Elizabeth Warren demanding that he should be “criminally investigated.” What got Stumpf in most trouble with Congress was his refusal to offer a view on whether the Wells Fargo board should claw back pay from him or Ms. Tolstedt. Of course Stumpf himself was also the bank’s chairman of the board. A week later, though, Wells Fargo announced that it would indeed claw back compensation from Mr. Stumpf. He would forfeit $41 million in stock awards, with Ms. Tolstedt forfeiting $19 million of her own stock awards, both also giving up any bonuses for 2016. On October12th, to no one’s surprise, Stumpf’s resignation as Chairman and CEO was announced. Things became worse when, on August 30th, 2017, Wells admitted it had found up to 3.5 million potentially fake bank and credit card accounts in total, significantly more than the 2016 tally. Congress, Wall Street, everyone expressed shock, and the bank suffered a credit downgrade from ratings agency DBRS. The bank’s stock fell 3%, on top of an underperforming trend in 2017. No head rolled this time, but most analysts stressed that Well Fargo’s reputation would be tough to repair.

The Trump administration took a number of steps to weaken the CFPB and its reach: For example, a provision allowing class action suits against large financial institutions was recently eliminated. When the CFPB head, Richard Cordray, announced he was stepping down at the end of November of 2017, Mick Mulvaney, currently the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), was named acting head of the CFPB on November 24. When a congressman in the House of Representatives, Mulvaney was one of the fiercest opponents of the CFPB, essentially questioning its very reason to exist. On June 16, 2018, Donald Trump selected Kathleen Kraninger, a White House budget official, as the nominee to be the next director of the CFPB. The Senate Banking Committee narrowly approved Ms. Kraninger’s nomination on August 23 of this year.

Reducing the independence and effectiveness of the Consumers Financial Protection Bureau makes sense for banks and Wall Street, but none whatsoever for Main Street. After all, the Consumer Bureau is the only federal agency that protects regular Americans in their dealings with banks. Since its inception it has returned over $12 billion to millions of people, by reversing fees from phantom accounts, moderating predatory fees on loans and mortgages of all kinds, and curtailing abusive debt collection practices.

- Why is Dodd Frank such a controversial law?

Overall, Dodd-Frank’s complexity (over two hundred rules overseen by a dozen federal agencies) was the reflection of a complex mess that took years in the making, culminating in the 2008 financial meltdown. As a financial channel television commentator once said, “it is hard to unscramble the eggs.” Such is the complexity of modern finance.

This complexity of Dodd-Frank is its main weakness, and why it is controversial. This is why Candidate Trump advocated a return to Glass-Steagal, a much simpler and clearer legislation. This is also why even conservative Republicans, such as Representative Jeb Hensarling, the chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, have advocated much simpler ideas to prevent a repeat of the 2008 financial meltdown, such as the idea that banks should be able to be exempted from most of Dodd-Frank, provided they built very high reserve requirements, or equity capital relative to debt. This means that they would agree to higher limits on how much of their activity could be financed with borrowed money.

Unfortunately none of these simple concepts is being contemplated today. Rather, we appear to be hostages to a regulatory tradeoff where we can have on one hand ever more complex regulations, galloping compliance costs, and less systemic risk; or on the other hand reduce regulations and increase risk. Isn’t there a way to extract ourselves from this dilemma, and use simple, high level standards and rules, that would give us safety in the financial sector without a whole bureaucracy of regulators, lawyers and compliance experts? This is the right time to ask this question. With all financial market indicators in record territory, very high price to earnings rations, and volatility indices at record lows, everyone may be asleep in terms of worrying about risk – could this prevent us from seeing the first clouds before the next storm?

Tags: "Untangling the USA...", Banks, Consumers, economy, Finance, Income inequality, Regulations, United States, US political trends, Wall Street